Terminate or accommodate? Litigation prevention is key

Will you terminate or accommodate that employee with difficult-to-manage disabilities? It’s one of the hardest decisions an employer has to make. That’s especially true right now when reduced business prospects may mean organizations need to cut staff. Terminating disabled workers over others is one of the riskiest moves. Litigation prevention is key when the choice is termination over accommodation – and that may mean sweetening the exit. A well-drafted severance agreement can all but eliminate litigation risk if you can persuade the departing worker to sign. However, getting a signature on a release shouldn’t be your first move. You must engage in the interactive accommodations process before drawing up the severance agreement. That’s the key to showing a judge or jury you followed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Your ADA reasonable accommodation obligations

The ADA protects disabled individuals from workplace discrimination, among other things. There are two major employment linked ADA protections. These are:

Non-discrimination

Employers may not discriminate against disabled applicants or employees in hiring, benefits, promotions or training. This is the non-discrimination aspect of the ADA. It obligates employers to look beyond disabilities when making employment decisions. An employer cannot reject a disabled applicant who can perform the job she seeks despite her disability. The disability is irrelevant under the ADA’s non-discrimination provision. It doesn’t matter if the disability may result in higher health insurance costs or time off for treatments, for example.

As part of their non-discrimination obligations, employers should never assume or ask if an applicant or employee is disabled. Instead, wait until the individual self-identifies as disabled and asks for an accommodation. This is especially important right now, during the COVID-19 pandemic, as employers prepare to re-open, bringing workers back from telework.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that employers identify “vulnerable workers” at heightened risk for COVID-19 complications. Many of these workers have disabilities like diabetes, heart disease or asthma that are ADA disabilities. Per CDC guidance, vulnerable workers should be placed in positions where they are less likely to become infected. For example, the CDC suggests disabled workers continue teleworking. It also suggests that customer-facing vulnerable workers be placed in more isolated positions like stockrooms.

There is one obvious problem with the CDC approach, which the EEOC acknowledges. Singling out vulnerable workers who also happen to be disabled likely violates the ADA. Before reassigning or otherwise treating vulnerable workers differently that other workers, wait until they self-identify. Then engage in the reasonable accommodation interactive process (see below) to arrive at the reassignment.

Reasonable accommodations

The ADA goes further than simple non-discrimination, though. It also requires employers help some disabled individuals by making reasonable accommodations for their disabilities. That employer obligation is supposed to level the playing field for disabled individuals who compete with those without disabilities. As long as accommodations are a reasonable burden on the employer, the law requires they be provided.

A reasonable accommodation is one that allows a disabled individual to perform the essential functions of the job sought or held. Employers must identify essential functions and exclude non-essential ones when determining what accommodation is reasonable. Generally, the employer gets to choose what functions are essential and which reasonable accommodation (if more than one) to offer. That’s true even if the disabled individual would prefer another accommodation.

To arrive at a reasonable accommodation, the employer must engage in an interactive accommodations process. That generally means discussing the disability, the individual’s needs and what accommodations are possible. Those discussions will generally result in an accommodation offer if a reasonable one is feasible. If not, the employer should carefully document the process and why no accommodation is reasonable. Typically, this is because the disabled individual cannot perform the essential functions of the job with or without an accommodation.

ADA, COVID-19 and reasonable accommodations

Let’s apply the interactive accommodations process during the time of COVID-19.

Jane: Jane has a body mass index (BMI) of 30 and has had a heart attack. She works as a cashier for a toy store but is on furlough. The toy store had closed when the governor deemed it non-essential. It will now reopen, following CDC guidance and state rules designed to maintain social distancing. Store capacity has been reduced and customers (except young children) and employees must wear masks. A plexiglass screen has been placed on the checkout desk, separating toy purchasers from cashiers. The store has called Jane back.

If Jane does not raise her possible disability and simply returns to work, her employer need do nothing more. That’s assuming its other actions comply with state and local reopening rules. However, Jane tells her manager she would like an accommodation of more time off. She points out that the CDC identifies a BMI of 30 as a COVID-19 risk factor. She also claims her heart attack caused permanent heart damage.

Her manager should start the interactive accommodations process. First, determine whether Jane is disabled. Her BMI of 30 means she is obese under CDC guidelines. However, until now, obesity is rarely viewed as an ADA disability. If he rejects her claim of an ADA disability, it’s likely she may sue. She may claim that having COVID-19 risk factors means she is substantially impaired in the major life activity of working. The safest course of action would be to accept her claim of disability.

The next step is to determine if there are reasonable accommodations that allow Jane to perform the essential functions of her job. Generally, more time off may be a reasonable accommodation. But so is a temporary reassignment to an open position. In this case, the store could offer to let Jane work in the stockroom. Remember, employers can choose which reasonable accommodation to offer.

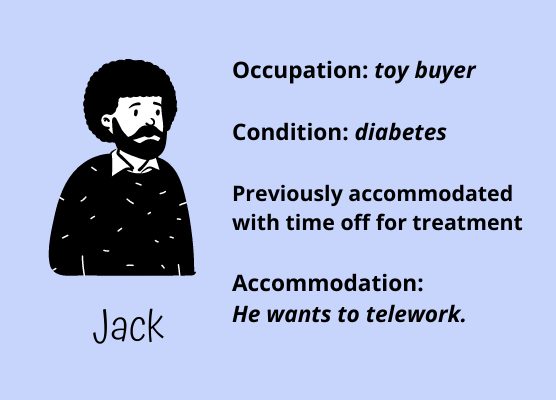

Jack: Jack works for the same toy store, but as a toy buyer. He has diabetes, which the store has previously accommodated with time off for treatment. Before the pandemic, he had a private office in the store. From there, he worked with inventory to determine what toys were most popular and profitable. He also regularly attended national and international toy shows. When the store closed under the governor’s pandemic order, he continued to work but from home.

Jack does not want to return to the store. He tells the manager he has successfully done his job from home. Jack notes that he is also a vulnerable worker and requests telework as a reasonable accommodation. The manager should begin the interactive accommodations process as with Jane. However, since it has already been established that Jack is disabled, the discussions should move to accommodations.

The manager rejects continued telework, noting that Jack has a private office. He does tell Jack that they will revisit other aspects of the job when toy shows again open. The toy store has likely met its reasonable accommodation obligations.

Crafting an effective severance agreement to prevent lawsuits

In both examples, the employer has likely met its ADA obligations. However, if Jane rejects the offer and quits or if Jack refuses to return and is fired, they may sue. In each case, they might argue that the accommodation offered was not reasonable.

To avoid a potential lawsuit, employers can include a severance agreement offer with their reasonable accommodation offer. Employees could choose to accept the accommodation or resign in exchange for the severance payment and promise not to sue. The severance agreement should include a very specific waiver in exchange for the payment. One caveat: Federal law and some states limit what kind of claims can be waived. Have your lawyer help you craft specific language to maximize your litigation protection.

Employers can also add other sweeteners in addition to cash to induce signing. For example, they could continue health insurance coverage for a period, provide a positive reference or other benefits.

WARNING: Severance agreements are contracts. They must conform to state contract laws. Be sure yours complies with state law. That’s another reason to get legal help. Plus, there are additional considerations if the employees are older than 40. Those employees are protected by the Older Worker Benefits Protection Act (OWBPA). The federal law prohibits you from using age as grounds for termination and targeting older workers for a reduction-in-force. Many disabled employees are also over age 40.

The OWBPA sets out exactly how you must structure a severance agreement. Any release must include some form of consideration like extra pay and:

- Be knowing and voluntary;

- Be written in plain language;

- Provide accurate information;

- Mention the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA);

- Advise the worker to consult counsel; and

- Provide at least 21 days to consider the offer and 7 days to revoke signature.